Agenda

Artikelen

Programma

Agenda

Artikelen

Programma

When we imagine a family, we often still refer to the implanted image of the nuclear family. When we look at the family we have to imagine an institution. The family has been constructed as a tool of the patriarchy and therefore suppresses both men and women. In this writing I want to decontextualize the nuclear family by examining the role of the mother. Knowing what made the mold will allow us to unlearn and reposition ourselves within the family. I wish to strip ‘mother’ from its social structure, and rather understand ‘mothering’ as the act of nurturing, of loving (which of course is genderless). Through this radicalizing of the Mother, I seek to challenge the normative and social implications of the family system that society continues to keep alive.

Feminist scholar Shere Hite writes, “To understand the family in Western tradition, we must remember that everything we see, say and think about it is based on archetypes that are so pervasive in our society – the icons of Jesus, Mary and Joseph. (There is no daughter icon.) This is the “holy family” model that we are expected, in one way or another, to live up to.” We must attempt to place the “family” against a larger cultural backdrop. I would like to address that when we are actively working towards the radicalizing of the known family structure, we will need to greatly consider the abolishment of the binary. Or at least the bending of it. In order for us to rewrite the narrative of the Mother and her counterparts we must see her for more than just her predisposed femininity. We must consider the Mother outside of her archetypes.

When the role of the mother is redefined, so is the entirety of the family. I will emphasize the need to abolish the outdated concept that “women’s predominant role in childrearing and domestic labor is their biological destiny.” When women are liberated from this predetermined position, there is room for the role of the mother to be redefined through “A multi-gender feminism in which the labor of the mother is not policed.”. I hypothesize that this change does not represent “the collapse of society”, but in fact its rebirth. This change is part of a transformation in both social structure and human relationships. By leaving behind the binary, we redefine the structure; we no longer see those of us who have wombs as obligated to reproduce, and we abolish the feminization of the mother.

When looking at queer culture we often speak about the notion of the “chosen family”. These queered homes hint at how motherhood can be liberated from the traditional values of ‘family’. As queer people we are much more likely to have been cast out from a community or family structure. This feeling of abandonment has led to the forming of chosen families. These chosen families are exactly the “radicalizing of the family” which I am suggesting. We see a form of closeness within these families that is “revolutionized by struggles seeking to ease, aid, and redistribute” a reality. A reality that makes space for each being to mother, and to be mothered; and makes care available for everybody.

I propose that we decontextualize the notion of the Mother, and consider that we can all be mothers. Motherhood is more than just the act of birthing and working for the placenta. The role of the mother can be abstracted and genderless. When we abolish the traditional roles of the family we can be liberated and find ourselves with endless possibilities of how we want to form our own “familial” connections. “Another family is possible” another kinship; a revolutionary one. “A world sustained by kith and kind more than by kin”. We must go forward with the idea of pluralism as something to be valued.

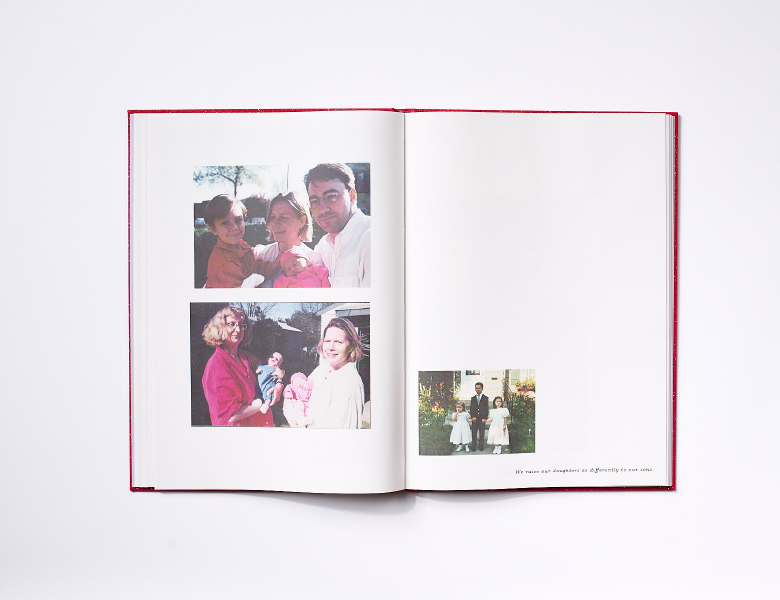

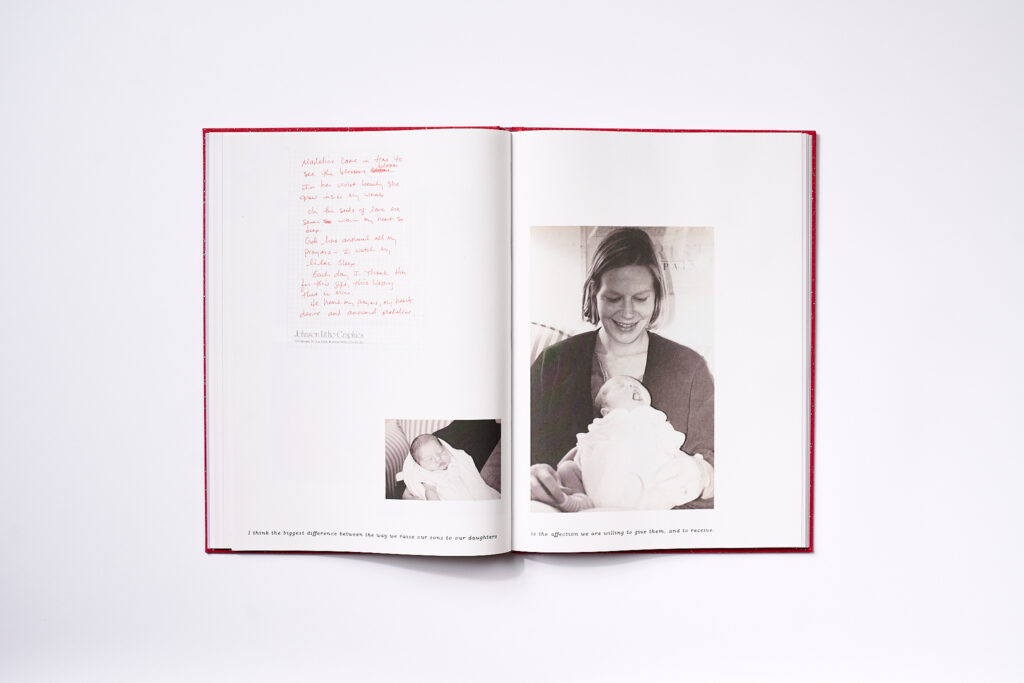

I think the biggest difference between the way we raise our sons to our daughters is the affection we are willing to give them, and to receive. Documentation of my BA thesis – Nuking the Nuclear Family.

Excerpt from Anger and Tenderness in Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution by Adrienne Rich

I have a very clear, keen memory of myself the day after I was married: I was sweeping a floor. Probably the floor did not really need to be swept; probably I simply did not know what else to do with myself. But as I swept that floor I thought: “Now I am a woman. This is an age-old action, this is what women have always done.” I felt I was bending to some ancient form, too ancient to question. This is what women have always done.

As soon as I was visibly and clearly pregnant, I felt, for the first time in my adolescence and adult life, not-guilty. The atmosphere of approval in which I was bathed– even by strangers on the street, it seemed– was like an aura I carried with me, in which doubts, fears, misgivings, met with absolute denial. This is what women have always done.

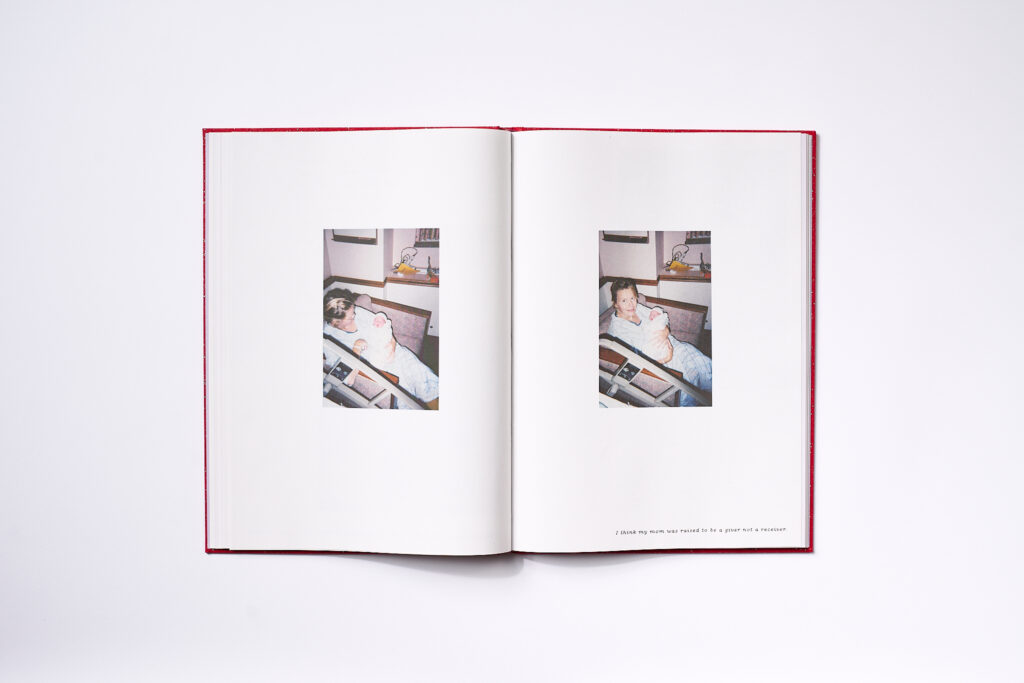

I think my mom was raised to be a giver not a receiver. Documentation of my BA thesis – Nuking the Nuclear Family.

Caring Kinships: Beyond the Biological

Simone de Beauvoir points out society’s hand in defining womanhood in her seminal text The Second Sex:

“One is not born, but becomes a woman. No biological, psychological, or economic fate determines the figure that the human female presents in society: it is civilization as a whole that produces this creature…”

We know that womanhood is a construct, not tied to biology; we know gender exists on a spectrum. If we queer gender and expand the definition of womanhood, we can redefine motherhood. Motherhood is currently tethered to femininity; most girls are raised to believe that Motherhood and the Nuclear Family are cemented in their future. Besides excluding people on the spectrum of queerness (of gender and sexuality), the Nuclear Family also limits the opportunities of the people it was created “for”: heterosexual cis people. To properly abolish the Nuclear Family and redefine it, we must reject the biological and social constructions of Woman and Mother. We must create a new familial vocabulary to include all kinds of partnerships.

Queer family– a structure that by definition defies the norm and the known– renders irrelevant the world’s impulses to control and classify women. Lesbian-coupled families are expected to answer a bizarre array of questions: Which of you is the “real” mother? Who is the father? Who is the man of the house? Who holds ownership? Who “wears the pants”? Who “brings home the bacon”? These questions are irrelevant when the subjects exist outside the male-female gender binary and the heterosexual binary. Monique Wittig suggests that queerness destroys the artificial construct of the “natural woman.” With two women in a household, there is no single Mother.

The feminist authors’ group Care Collective defines the significant elements of second-wave feminist struggle during the 1970s as the “burden of childcare, its devaluation as a practice, and the way it worked to preclude women from participating in public life.” Second-wavers offered solutions to this struggle through collective living arrangements, with and without men– spaces which allowed for all domestic labor to be shared equally. These homes were often called “families of choice,” more recently known in LGBTQ communities as “chosen families.” The term referred not directly to childcare but to any relationships which existed outside of the biological family. Because “non-normative sex or gender expressions could (and still can) cause a person to be rejected by their biological family,” many members of the queer community moved to gay neighborhoods out of necessity. These neighborhoods were made up of family-like relationships with both friends and lovers, and allowed for the fulfillment of each person’s caring needs. Forming chosen families was also a politically radical act and a significant factor in queer liberation. These homes were the blueprint for expanding relationships of care and intimacy beyond those acknowledged by heteronormative society.

When we imagine a family, we often still refer to this implanted image of the nuclear family. This structure is no longer the norm– and may have never been. Today, families are made up of blended and complex kinship relations, comprised of “divorce and remarriage, lone parents, queer relationships, polyamorous families, foster families, migration of family members, non-family households, multi-generation households, empty nesters, and more.” We must learn to value the care that exists outside of the Nuclear family.

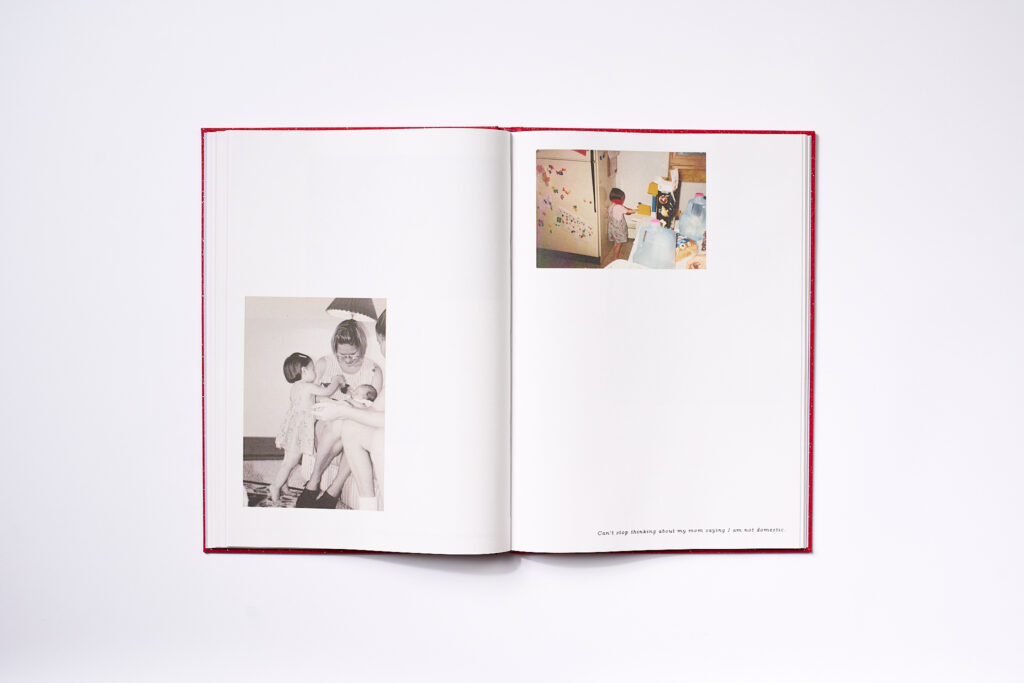

Can’t stop thinking about my mom saying I am not domestic. Documentation of my BA thesis – Nuking the Nuclear Family.

The Mother is automatically assigned the labor of care. Mothering is “still upheld in our culture as the archetypal caring relationship, but one whose practices are so rigidly idealized that they may often burden even those women who desire the role and have the resources to perform it.” We must re-distribute this labor among the family: we must consider that we can all be mothers, and all family members can experience and practice care. If we build care-full homes and foster networks of intimacy, we create a more inclusive notion of mothering that better serves the Family. The Care Collective argues that “we must not discriminate when we care”: our ideology must, then, holistically extend to all familial situations. For instance, we must acknowledge that not all women want to become mothers. We must value adoption, surrogacy, and guardianship as much as we do biological motherhood. We must value long-term caregivers– step-parents, nannies, foster parents. We must abolish the concept that mothers must have experienced birth or have biologically conceived a child in order to claim their status. We must build spaces that support the work of “social reproduction, care-giving, and child-raising in creative, even feminist, ways,” based around the needs and desires of all families and kinships. We must enact author Leslie Kern’s vision of the feminist city in our public spaces and our private homes to liberate Mothers from the burden of caring alone:

“A feminist city must be one where barriers—physical and social—are dismantled, where all bodies are welcome and accommodated. A feminist city must be care-centered, not because women should remain largely responsible for care work, but because the city has the potential to spread care work more evenly. A feminist city must look to the creative tools that women have always used to support one another and find ways to build that support into the very fabric of the urban world.”

Mothering is an act that should not be relegated and reserved for women, because to nurture and to love is, of course, human– it is genderless. When gender is queered, we abolish concepts of ownership, conformity, and designated labor within the home. When we reject the image that has been given to us, our choices, options, and alternatives for birthing and child-rearing multiply; the possibilities of mothering expand. To mother is to care, to nurture. To love, and be loved. We all have the capacity and the right to care, and therefore to mother.