Agenda

Artikelen

Programma

Agenda

Artikelen

Programma

“As far back as my memories go, I was always painting and drawing. When I was still a child I spent many hours of the day with my pencil, rather then playing with dolls. So, since I was six years old it was my dream to be a painter. Then in high school I studied painting and it was then that I read a book about the life of Vincent van Gogh and this was very inspiring to me. After that I went to university in Teheran where I studied painting. I was doing still lives then, but slowly this started to change, the paintings started to get these sexual themes. It came, I don’t know, unconsciously and there were penises and cunts and I realised: I cannot show these works here. So I decided to go abroad. I said to myself: I will go to a free country and have shows and do whatever I want. I will show cunts and dicks and not care about anything. First I applied for two universities in the USA, but they both rejected me. Then a friend of mine, who was living in the Netherlands said: why are you sad, just come to the Netherlands, and she found St. Joost for me and one afternoon I sent my portfolio and my papers and they let me in. I didn’t have any idea about the Netherlands, or St. Joost. Nothing. I was just super happy, you know. Now I could go abroad and show my works.

But when I got here I also started feeling homesick. It was a mixture of different feelings: I was happy to work freely and to be able to express myself, but at the same time I was so sad, because I felt that I’d left my motherland and I was lonely and homesick.”

So after your studies you went back to Iran?

“Yeah, you know. I was feeling so safe, and feeling like I could do whatever I wanted here. I didn’t have to think about consequences or what would happen in the future. But when I decided to go back to Iran, I had to stop all these things, because it was too hard. So I started to do fashion design, because it’s also kind of art and it was what I could do to stay alive, to earn some money. But after my time in the Netherlands I really felt that I was missing something inside myself: this is not Lala. I need to do these kinds of things.”

She points at the drawings covering the walls and floor of the studio.

“Three years later I started making these kinds of drawings again in a little notebook that I kept to myself. These sexual themes are something very important and very personal to me. There is anger in it that I feel because of experiences in my past, experiences of abuse. And as an artist I needed to express these somehow. So I had this pain in me, but when I draw this pain and this anger, it works as a painkiller. I it was self curing. I just did it for myself, not for anybody else. You know, I’m not interested in making big statements. I’m not an activist. I’m not doing this for the world. Though when I came to the Netherlands I did start looking up. I started looking at things going on around me. I started comparing lifestyles. For example: when you’re born in Iran, which is an Islamic country and you have no choice but to accept the rules, and you unconsciously face many limitations. But at the same time I was born, someone else was born in the Netherlands, and someone in Africa. So there are many differences between our lives, but we’ve lived for the same time in the same world and I believe we are similar at the core. I would say that the core of creation is sex.”

“In the beginning I didn’t feel that way about the Netherlands. Instead I felt a strong equality between men and women, because I didn’t have this experience of being with western people. But when I went outside and I met guys here, I understood that this is not just something about regions; it’s not about Iran or Afghanistan or the USA or Europe. It’s something that they’re controlling, you know. I’ve met some Dutch guys and at first they want to help you, and they’re polite, but as time passes you see that they’re only looking to have sex and an orgasm, that’s it. Maybe I’m dark for saying this, but it has been my personal experience both in Iran and here. Though here it’s still better, because at least they try to have some self-control and they don’t come to you directly saying: hey, I want you to be my lover and have sex with me.”

Do you think this can change? Do you think there are fundamental differences between men and women?

“Yes, fundamentally. But it’s beautiful. These differences between men and women are something beautiful. The body of the woman is the most beautiful creature God created, on the other hand you have the strong bodies of men, that’s a form of beauty too. And the differences are lovely, so lovely. Just imagine the world with all the same bodies and it’s full of women or full of men. No, that wouldn’t work.”

But doesn’t this idea that women are pretty and men are strong sort of validate the idea that men are dominant and women should be submissive?

“But men and women are not the same. There are some feminists who want to say this, but I wouldn’t say this. I would say that, in sex, women are more dynamic. If you look at how women get orgasm and how men get orgasm, with women it’s more complicated. Men just come.”

I don’t agree. Just because I’m a men doesn’t mean things always work a certain way. Men can identify with stereotypical female qualities and vice versa, no?

“But the majority, though.”

But then you’re talking about statistics. Isn’t it dangerous to talk about people that way?

“Dangerous?”

Because you’re reducing them to two possibilities, whereas in reality people are not averages, but fall somewhere within a spectrum.

“What do you mean?”

I try to explain. Eventually she hands me her phone with Google translate opened on the screen. I type in the word spectrum, hoping that the arabic script appearing on the screen means the same, I hand the machine back to her. It doesn’t seem to help very much.

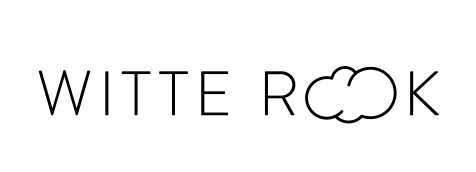

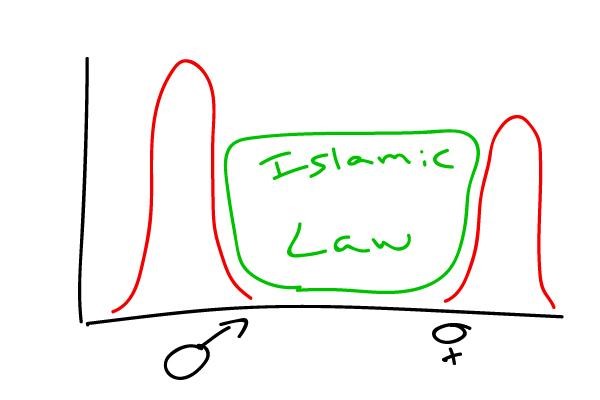

Wait, I’ll draw it. So, when you separate men and women, it looks like this:

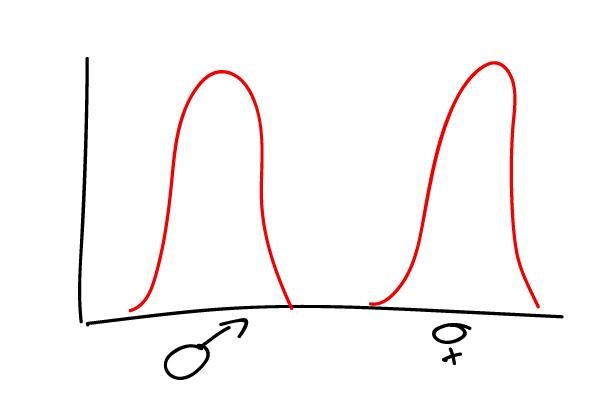

Everybody on their own island. But in real life it’s more like this and you can be anywhere you want, it’s just that women tend to be more on the left and men more on the right:

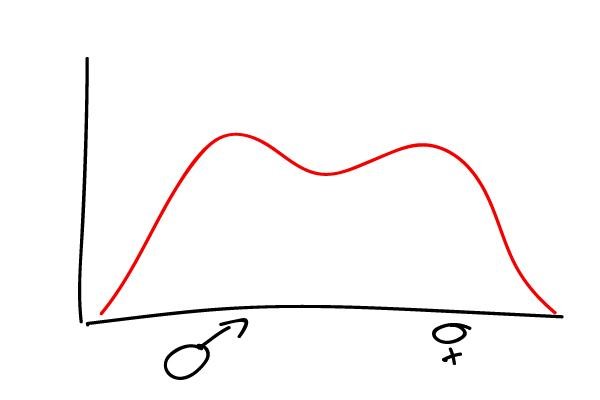

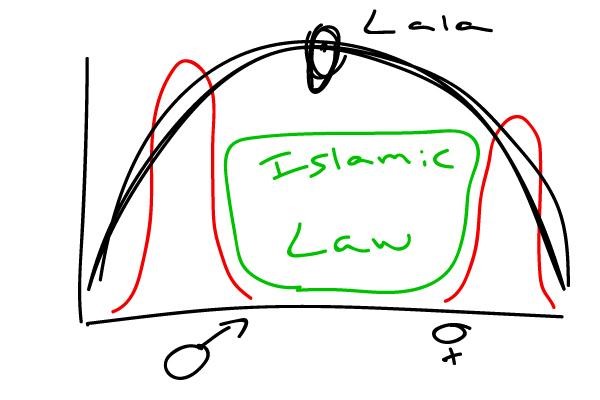

“No, I don’t believe in this. I think it’s like this:”

Why are the women lower?

“Because I see it. I see that as a woman. I see that as a woman who is also a rebel in her own country, who doesn’t want to accept and fight these rules.”

Are you in there too?

“Yeah, this is me, though I also have all these thoughts and all these artworks that I make the challenge this life. I’ve seen the huge differences between men and women and I know that if you go and ask, they say: no, we are equals, and you are more powerful and bla-bla-bla, but what I see, as Lala, in reality, in this world, in this time: I’ve seen it like this. And this is something that, when I’m hanging out with men, I wouldn’t say, because I still want to show that I am powerful as they are and that we are the best. But when I look inside I see weakness. Being a woman, living as a woman, it is hard. If you are born as a women in an Islamic country, it’s 90% harder. So just imagine how powerful we can be. But then, when I went abroad and saw the same things, it made me wonder: how strong can I stay? What am I doing it for?”

It appears to me that this gap you drew is held in place by Islamic law, whereas western law wants to become something that doesn’t have any gap.

“Yes, totally. The thing here is that at least they say, or to act as if, they want to destroy this gap between men and women. But Iran and some other countries live in another time, like when churches had this power in Europe and it resists taking power away from men. The good thing here is that they don’t have that resistance. But some then say things like: the future is female, and that’s funny. Yet at least it shows that they want to do something about this, they want to act or say something nice for me to hear as a woman. But they still don’t have this equality and I don’t think they’ll ever get it. I don’t want them to be equal, I don’t think it’s beautiful. I would love to see equality between men and women, but to still have this small difference.”

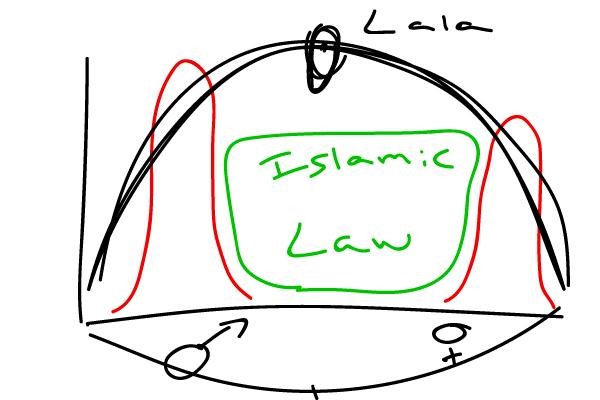

Different but on the same height?

“No, you see, I’d put the men a tiny little bit higher. But the difference can be much smaller.”

What would happen if women were higher? Just a smudge.

“Let me think… I don’t know… I really don’t have any idea. Maybe this is something that went to my believes, because I always see men as higher. That was a good question, I’ve never thought about that. But I wouldn’t like it, because I see men as more powerful. That’s how I’d describe men. But sometimes I have this power.”

”Sometimes I’m on top. Especially when I’m here and I can work and express myself and say all these words in English that I’m too shy to say in Persian. So when I’m here I have this power and I’m Lala and i don’t care what people say or think. But when I go back to Iran, it becomes like this. There they have the power and I’m down here.”

Below?

“Below the bottom.”

You feel like a different person in Iran?

“Yes, for example when I socialise with people I don’t say that I’m an artist, and if I do I’ll say I’m a fashion designer. Because I don’t want people to see my artworks and judge me.”

Would you want to change Iran?

“No. No. I don’t have any hope to change it. In a way I’ve already accepted that it’s like this. I was born after the revolution, which was in ’79, and I was born during the war with Iraq. It was war for the first six years of my life. That’s why I hate war. I still get scared by loud noises. It reminds me of that time, because we would live in apartments and we would hear the bombs dropping, the big alarm would start and you’d have to go to these shelters. This had an effect on me. I don’t want a war. I got used to the Islamic laws in Iran and I don’t have the power to change this government, to change all these things. If I want to stay here, in a free country, I could. As a refugee. And I would be able to express myself and make my works. But I don’t want this, because it would be the easiest choice. If I stay here, what would I have to say? What would I have to show? I cannot decide, because it’s what made me.”